Little Lady was buried last week. She was at least 23 years of age. Her pale gray calico-ness showed up about the same time that Steve secured the last piece of lumber on the front deck. She didn’t leave the deck so we opened the door. After that, she never left the house except for vet visits and to step out and turn right back around to inside. She was ridiculously healthy, opinionated and acrobatic. We figured that she would scramble up the stairway banister or doorframe one day and check out in mid-journey one day. And that’s almost exactly what she did.

But this writing isn’t about Little Lady. Other than living in the house that sits apart from the farm animal sanctuary here, she wasn’t of The Quarry Farm. This is about what happened after she died.

We cried, grabbed a pick axe and shovel and took her body outside to bury her in the frozen ground under the white pine needles in the north corner of the pasture. She didn’t particularly like other animal company so we didn’t bury her near anyone else. We joke that someday someone will excavate this property and shudder, wondering, “Who WERE these people?” But the remains of a little cat will be there, all by themselves. The excavators may attribute some sort of deification to her.

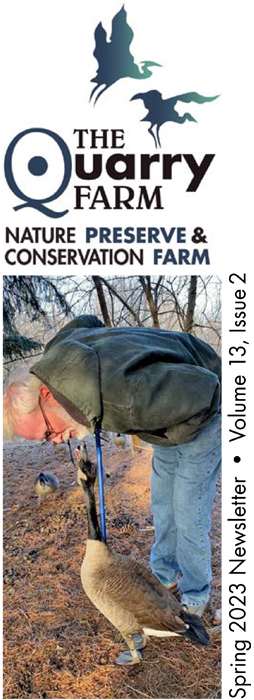

The donkeys came first, stepping slowly up the slight incline from the lowland. Then the goats. Then Willy the three-legged sheep. And for the first time, in all the physical goodbyes that one has to make on a sanctuary, the geese came. Not Gigi and Henry the domestic Emden and China White, but the Canada Geese. They were delightful, deep flood pools in the north lowland to race-fly across. But the seven geese placed her for soft-release walked slowly up the hill, murmuring to each other with their long necks snaking out in front of them. T, the largest of the little flock, stood on Steve’s feet while I replaced the soil.

I don’t know why they always come. It’s more than out of curiosity and strange odor, of that we’re sure. When Mister Bill the Giant Goat died, everyone—every single one—gathered around his grave. One of the goats knocked the shovel and the first load of dirt out of Steve’s hand.

We bury as deep as we can in order to prevent the unsettling sight of a corpse being predated. In 20 years though, it hasn’t happened. The pine needles were scattered and smoothed over this most recent grave. I looked at it today and you would never know that the spot had been disturbed. The pigs root constantly in spring for green shoots. The chickens follow up for worms and grubs. But they have yet to touch a burial spot.

Maybe it’s the disruption in energy, neither created nor destroyed. I don’t know. I don’t know that any of us humans will ever know, because we seem to think we know it all already. But they do, simply and beautifully.

Keep making more connections. Download your copy of the Spring 2023 newsletter by clicking on the cover.

Bill took to the increased menu with relish. After a week of antibiotics, he was strong enough to say no way to the syringe. He licked his bucket clean before joining the other goats to nibble tall goldenrod and mulberry leaves in the lowland. But there was more going on inside his barrel chest, after all. Several days ago, Billy couldn’t stand. It took two of us to walk him to a bed under the pines where he could be in shade and good company. Dr. Babbitt was scheduled for a Friday house call. The plan was to fill Bill’s red bucket with taste treats before a final injection and release.

Bill took to the increased menu with relish. After a week of antibiotics, he was strong enough to say no way to the syringe. He licked his bucket clean before joining the other goats to nibble tall goldenrod and mulberry leaves in the lowland. But there was more going on inside his barrel chest, after all. Several days ago, Billy couldn’t stand. It took two of us to walk him to a bed under the pines where he could be in shade and good company. Dr. Babbitt was scheduled for a Friday house call. The plan was to fill Bill’s red bucket with taste treats before a final injection and release.

My ears popped as we climbed out of the Mississippi River Valley and rolled through greening hills and fjords toward Rice County, Minnesota.

My ears popped as we climbed out of the Mississippi River Valley and rolled through greening hills and fjords toward Rice County, Minnesota.